Like a London taxi driver, Tara Viggo has The Knowledge.

And like that driver, her secret ninja power is a subtle but mighty one.

Tara Viggo knows how to translate the language of fashion - cut, fabric, drape - into the paper patterns fashion houses use to make beautiful clothes. She knows how clothes should fit, and what kinds of fabric would work best with a particular construction to make it most flattering. It’s knowledge - and an eye - that she’s spent years developing through sheer hard graft in London’s fashion industry.

Now, she’s turning that knowledge into patterns you can use to make simple, stylish, wearable garments at home. (And there’s not-surprising bonus, given her background: They have a style edge.)

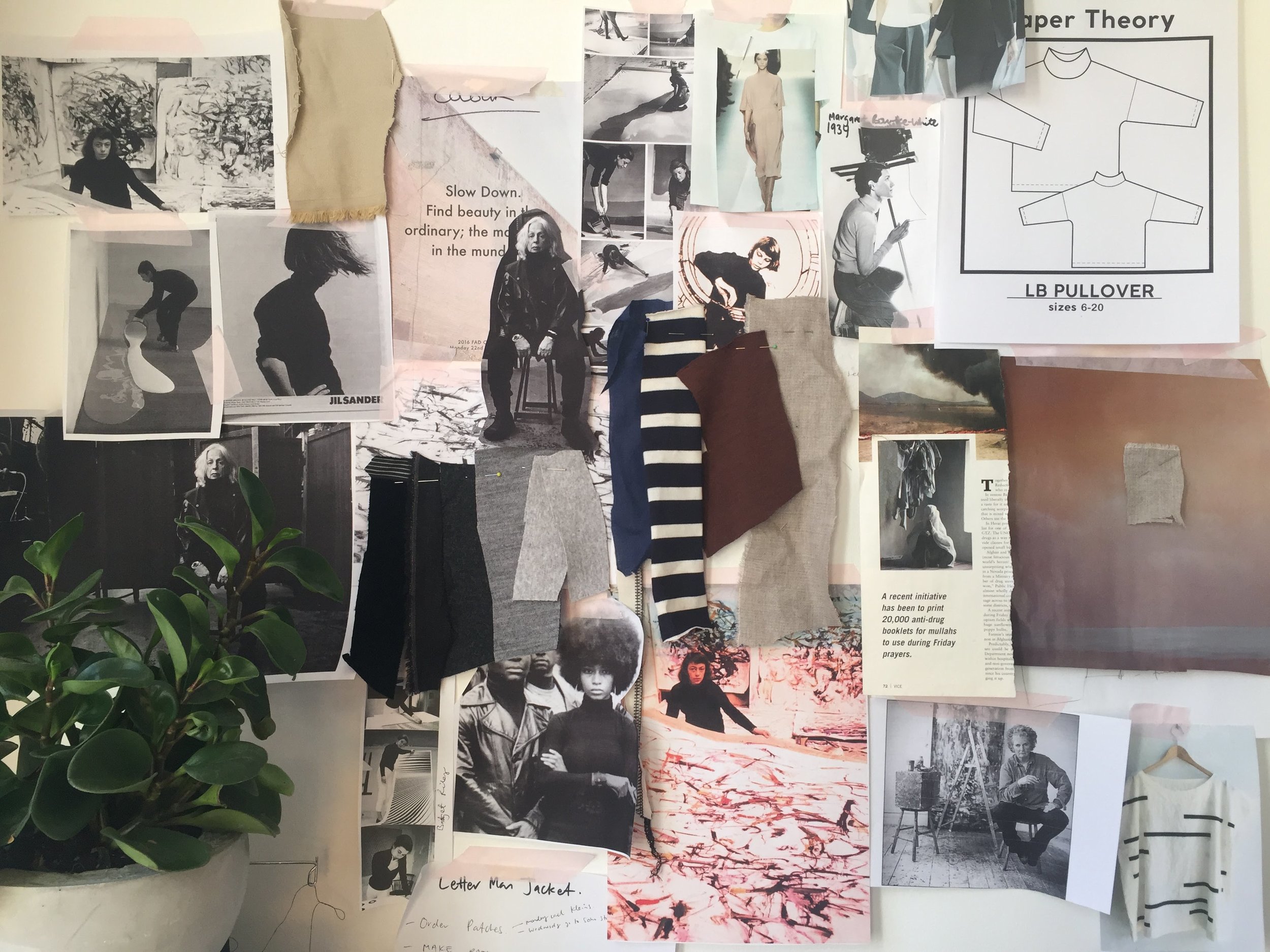

Viggo, 35, is a Cook Islands-born, New Zealand-reared pattern cutter who has lived and worked in the London fashion industry for nearly 11 years. Last year, after a decade spent cutting patterns for designers ranging from the High Street to couture, she launched Paper Theory, where she sells straightforward patterns aimed at home sewers. Her goal? To enable people to build a simple, flattering, eminently wearable AND stylish wardrobe that puts an emphasis on sustainability.

The Kabuki tee - as modelled by the designer

Paper Theory, which Viggo manages while still holding down a busy schedule of work for fashion houses, was born from a desire to have more ownership over her time, and as a way of getting the patterns in her head out into the world. After she had logged yet another late late night at work, Viggo’s boyfriend urged her to find a way to cut down on her punishing schedule and indulge her own creativity. She found herself thinking back to her childhood - and home sewing. “I remembered when I was quite small my mother would let me pick the patterns and she would make my clothes.”

But immersed as she was in the world of high fashion, and logging long hours, Viggo had virtually no idea of the renaissance of home sewing in recent years, fuelled in large measure by the internet. Blogs, Instagram, independent pattern makers, print-on-demand fabric companies, YouTube videos - it’s all there.

Viggo was staggered by what she saw, and spotted a gap for the kind of patterns she had in mind. The brand represents an extension of the direction she took her career a few years ago - towards sustainability and enduring style and away from fashion with a shelf life best measured in days. “There aren’t many of those pattern brands that have a sustainable edge and that’s something that’s really, really important to me,” she said.

Early in her career, after a couple of years working for fast fashion brands, Viggo found herself at a crossroads. She was upset about the high social cost of fast fashion - the well-documented stories about working conditions in some factories, the toll on the environment, the waste. She was ready to quit the industry altogether.

“I was going to leave fashion and I was going to become a landscape architect. And then I thought, actually, I can’t just leave this problem, because if I walk away the problem still exists, and I should do something that encourages this to get better. That was when I decided that sustainable fashion would have to be one of my biggest priorities.”

So she started working only for fashion brands that work with small factories and put an emphasis on ethics and sustainability. Then she took a big step in her personal life: “Last year, for New Year’s Eve, I set myself the challenge of not buying any new clothes.”

Viggo at work in her home studio in London

It was a great experience, Viggo said - with benefits that included liberating her from thinking about shopping, and worrying about what she might be missing out on in the sales as the fashion seasons turned, for example. “The mind tax of shopping is quite heavy, and I hadn’t really noticed,” Viggo said.

“The biggest surprise was, I thought it would be a year of sacrifice and longing, but in the end I actually gained more than I gave up. I reclaimed a lot of wasted time and I gained a huge amount of freedom. Freedom from thinking about what I wanted or needed or how I could make my life better by acquiring ‘things’. I actually feel liberated from the hamster wheel of consuming, and it’s a perspective that has transformed the way I will think about shopping forever.”

Viggo also wants to use Paper Theory to help people manage the cost of building a sustainable wardrobe - because the retail cost of sustainable, organic fashion is still high.

“Sustainable fashion is great, but in England there’s quite a class problem. It’s expensive. Choice is a luxury, and not many people have the luxury of choice. They’re defined by their income, and to ask them to sort of contribute to making the world a better place when they’re already getting shafted is a big ask,” she said.

“I just wanted there to be an alternative choice. It would be really nice to have really clean, simple basics so you could just pop off and buy a metre of really beautiful organic fabric and put that into your T-shirt. And you could have it be not too hard to make, and build the basics in your wardrobe. You can still buy special pieces from whoever your favourite designer is, but it’s a nicer way to fill the gaps.”

Building a wardrobe of essentials is just one more way to gain some independence from the fashion merry-go-round and to indulge your own creativity.

“The cost of fashion is really high - the social cost, the true cost. The pricetag’s going down but the cost is going up. Even I find it difficult. It’s hard when I’m faced with a three-pound white T-shirt from H&M which looks the same as a white T-shirt from a sustainable brand which would be like 50 pounds. It’s tough.”

Viggo is staunch on the details, and ensuring that time spent sewing with them will be time well spent. She spends a lot of time looking at how clothes fit, both online and in her daily work, and this means she’s well aware of the importance of getting the things right.

“A lot of home sewers won’t see the finer fit problems, but to me they’re quite jarring,” Viggo said. “It’s not like going off to the shop and spending 40 quid on a T-shirt and if you don’t like it, you don’t wear it. You’ve committed an afternoon to fabric shopping and then two days to actually sewing something together and then for it not to look nice, it’s such a tragedy, I think.”

She continues: “I’m really precious about my time - I get really upset about people wasting my time, so I couldn’t ask that of somebody. For a lot of home sewers, their eye isn’t finely tuned enough to notice that the balance is a bit off perhaps, so they won’t see it.”

Viggo earned her stripes in the fashion world through hard work and determination: While studying fashion design at Otago Polytechnic in her hometown of Dunedin on the South Island of New Zealand, she was offered the opportunity to head to Milan for a one-month internship at Marni. It was her first time overseas and opened her eyes to what was possible.

“Growing up in New Zealand you felt like the real fashion world was quite far away,” she said. “I knew that New Zealand had a great fashion industry, and have always been really proud of New Zealand designers, but I did feel like that luxury catwalk thing was very far removed for us in New Zealand. I didn’t know anybody who had gone and worked internationally, and it wasn’t until I spent the time at Marni that I could see that it was definitely possible.”

After graduating she took herself off to Melbourne to start her career. But she couldn’t crack into the industry there, and after a year of working in cafes she decided to pack herself off to London. It was there she found her career - by challenging people’s perceptions and making herself indispensable.

“The people were quite dismissive about having a New Zealand qualification - there are two or three really big schools in London and it’s quite a small club, and unless you’ve come from one of those schools they’re really not interested in you. What does a New Zealander know about design? It was quite hard, and that’s kind of how I ended up becoming a pattern cutter.

“I got into some studios but only as a studio assistant. Nobody would let me do anything real - I was just kind of making tea, sweeping up, doing some cutting. I could see around me that they were really short of pattern cutters, and the quality was terrible. What I had picked up at design school was better than what a lot of the junior pattern cutters in London were doing.”

“The biggest surprise was, I thought it would be a year of sacrifice and longing, but in the end I actually gained more than I gave up. I reclaimed a lot of wasted time and I gained a huge amount of freedom. Freedom from thinking about what I wanted or needed or how I could make my life better by acquiring ‘things’. I actually feel liberated from the hamster wheel of consuming, and it’s a perspective that has transformed the way I will think about shopping forever.”

- Tara Viggo on the year she gave up clothes shopping

So she remade herself into a pattern cutter - a job, she admits, that few understand. “Nobody knows what I do. When I meet somebody in a bar and they ask, what do you do, and I tell them, they can’t even fathom it. I try to describe what I do, and they go oh, I didn’t know that was a job.” She pauses and chuckles. “Yeah, nobody does.”

In her both her day job and her new venture, Viggo’s calling on deep roots - both her mother and her grandmother were home sewers, and skilled enough to make their own wedding dresses.

But it took a while before she drew the connection between the work she’s doing now and the skills her mother and grandmother used over a lifetime. “I wanted to be into fashion. I thought what my mother was doing at home wasn’t real fashion.”

Fuelled by a love of punk rock and punk style, Viggo and her friends would rifle through recycled clothing bins and come out with clothes to take home and transform. She laughs at the memory: “We’d put my skinniest friend in through the slot in the clothing bin, and we’d pull out what we could find, and we’d chop it up and make outfits and stuff. We’d literally hold her feet and she would rummage through.” Out would come men’s corduroy trousers, shirts, anything that could be used to make up punk outfits.

“That’s how I got into it, and when I went to fashion school my sewing was terrible. The sewing teachers gave me a really hard time. I thought, it doesn’t matter, I’m going to be a designer. But as we progressed through the year I realised it didn’t matter how good my ideas were because I couldn’t express them. I would have to learn how to sew and I would have to learn how to pattern cut, so I took it quite seriously and I got sort of obsessive about learning the rules and the technical skills.” She’d learned one of the biggest lessons for almost any creative pursuit: “You can’t break the rules until you know them.”

Viggo found her way into pattern cutting through sheer persistence while working as a studio assistant. “They were looking for a pattern cutter but they refused to give it to me. I said to them, please let me have this job, I can do it. One of the designers took pity on me, and she said you can do some of the work in the evenings. I kept bringing it back, and everything I did was better than all the pattern cutters who were coming in and trying out for the job. Eventually they said, oh fine, have a job.”

“It was just being really persistent. Nobody’s looking to pay somebody who’s never done anything before: You have to have a bit of luck and a lot of persistence, I think.”

LB pullovers in three versions.

Because Viggo was on a visa, she knew she had to make it work and that the clock was ticking. Her first job paid her less than minimum wage, so she worked in bars at night to cover the gap. Slowly she worked her way up to better and better fashion houses, and now divides her time between J.W. Anderson (challenging designs and a hectic environment) and Erdem (“everybody speaks in hushed voices”).

Listening to Viggo describe a typical day, you realise that she really does have a special skill - she’s able to give three-dimensional life to even the most abstract concepts in a designer’s head. She’ll get briefed by a designer, then return to her desk, some lengths of fabric and a mannequin, and get to work on the silhouette and the proportion. Then she’ll call the designer to have a look and they’ll talk through how things are going so far. “The designers are quite vague, and we sort of have to try and interpret each other. They’re very airy and I’m talking about millimetres.”

She realises that this skill of translation is crucial to her success. She can turn concepts into clothing just by listening, and by interpreting all sorts of clues. “It’s probably one of the biggest skills outside of the cutting that’s involved in my job,” she said. “As a freelancer I move around a lot, so I don’t know all of the designers. Sometimes they’ll give me a brief and I’ve only met them for literally three minutes. And I have to try to understand who they are, what they might want and what their taste is, having never met them, just from a drawing and just from a few words.

“It can be really tricky. I have to try and take from what they’re wearing, what they might feel about clothes. And from their body language, how they’re standing: do they like their clothes to be restrictive or loose? Once I get to know a designer, if I’ve worked with them for a few weeks, then it’s great and it’s really enjoyable.”

One designer, memorably, would bring in photos of ceramics, or waterfalls, and talk Viggo through the vibe of what she was after. Sounds impossible? It wasn’t - but it did take some time. “It was so difficult, but I worked with her for a long time and we managed to understand each other quite well, and some of the work i did with her has been my favourite. But it took a while to understand how to get, from a picture of a landscape, the mood she was trying to get across for the fit of the garment.”

There’s another big difference between Viggo’s fashion work and Paper Theory. When it comes to her own line, the designer has the average woman in mind.

“There’s not really much consideration for anyone who’s not a model size [in fashion],” Viggo said. “I’m using myself for Paper Theory. It’s been such a long time since I’d made clothes for myself that it was quite tough. I’m a 14 and I’ve been making stuff for size 6s. It has to feel nice. I imagine everything feels nice if you’re a size 6.”

She’s got two patterns on offer at the moment. She started with the Kabuki Tee*, a fascinating construction that results in a shirt that’s incredibly easy to wear, versatile and elegant. “I wear mine all the time - it’s such an easy piece.” You can make it using knits or woven fabric. “In linen it’s my favourite. I have a white linen one - I wear it as a T-shirt, and I can wear it to work, too.”

The LB pullover is her second offering, and whilst it’s not yet as popular as the Kabuki Tee, she believes it’s even more versatile - it could be a T-shirt, with short sleeves, long sleeves or no sleeves, or lengthened into a dress.

“The possibilities for that are quite enormous. I almost look at it as a block. I’m going on holiday soon and it would make a really easy shift dress. I could almost make an entire wardrobe of that.”

And that’s what Viggo would like to see: “I want people to have a shape that’s easy for them to make that they can use as building blocks for their own wardrobe.” To help people get the most from her patterns, she recently posted instructions on the Paper Theory website to step people through how to lengthen her shirt patterns into dresses. There's also a video tutorial illustrating exactly how to sew a right angle - a critical skill to execute the Kabuki tee.

Her other hope is that by sewing their clothes at home, people can get garments that really fit their own bodies, rather than being forced into the sizing grades offered up by fashion houses.

“That to me is the biggest plus for sewing,” Viggo said. “I’m really surprised that most sewers are not noticing that that’s the advantage that they have over the rest of the world. They can make something that looks so good on them - and they don’t take the time. A really small adjustment to a pair of trousers is the difference between looking like you’ve got a banging butt and great legs and looking like a frump. It can really make a huge difference.”

This is the value that Viggo’s disciplined, trained eyes can bring: “I scroll through Instagram and I think, 'Oh, if you’d just put an extra centimetre in that bust that top would look really great.' That’s the majority of my job, actually. I’ll make a style for the designer and then spend the rest of the week tweaking and changing. You learn a lot from that, so maybe that’s the knowledge I should share.”

Update: In 2021 Tara renamed the Kabuki Tee, and it is now known as the Block Tee. She did this because she no longer felt it was right for the tee to bear the name of a garment so important to Japanese culture. As she wrote in an Instagram post announcing the change: “My understanding of cultural appropriation is much deeper now than it was four years ago and I no longer feel the name is appropriate - so I have decided to change it.” There’s more on the change on her blog.

Helping teens learn fashion and design

For the last five years or so, Viggo has spent more than a few Saturdays giving back by teaching pattern cutting and sewing for a charitable organisation called F.A.D., which helps young people learn the ins and outs of all aspects of the fashion trade. She tells it this way:

“They are such a fantastic charity. They hold lots of workshops for young people. Every year they run a four-month programme which I volunteer at on Saturdays. The students design their own outfits and we help them pattern-cut and sew it from scratch. It helps them develop a portfolio for college, and they have a runway show at London Fashion Week to show their final designs.”

“It’s really the most incredible thing ever. Working with 16- to 18-year-olds is quite challenging, but I get so much back from the students. They have such fresh eyes and perspective - they challenge everything you say, EVERYTHING. It always makes me re-look at my perspective on fashion, my methods of construction and the way I do things, and keeps me creatively on my toes.”

All photos courtesy Tara Viggo